Yusuf Birader

Book Review: The Black Swan

TLDR

- Our history is dominated by a small number of unpredictable, extreme, retrospectively explicable events known as Black Swans.

- There exist certain human traits which blind us to the existence of Black Swans. The includes our tendency to derive generalisations of the future from particulars of the past, to concoct causal narrative involving a sequence of facts even when one does not exist and our neglect of silent evidence in history.

- Ignoring the possibility of Black Swan events can have large consequences. For example, the failure of financial forecasting models to account for them has lead to large miscalculations of risk, causing financial crises.

- We can improve our odds of success by exposing ourselves to positive Black Swans.

Read on for more details…

Review

The Black Swan was a thoroughly enjoyable read. It provoked me to question many of the assumptions of the world we often take for granted.

How the book changed me

- I have more epistemic humility and have learnt to recognise the limits of my knowledge. In particular, our knowledge of the future is fundamentally limited- it’s better to be prepared than to plan.

- I try to embrace when things don’t go to plan. Trying to precisely architect one’s life to hit certain goals is tiring and limiting. Be process-oriented, not goal oriented. Separate labour from the fruit of labour. Be more serendipitous and make the best of the inherent uncertainty in the world.

- I’ve learned the importance of being skeptical when predictions have the ability to harm you and be indifferent when they don’t.

How could the book be improved

In places, the author uses excessively complex language to describe simple concepts. This can hurt the clarity of the message.

Top Quotes

Missing a train is only painful if you run after it! Likewise, not matching the idea of success others expect from you is only painful if that’s what you are seeking.

My biggest problem with the educational system lies precisely in that it forces students to squeeze explanations out of subject matters and shames them for withholding judgment, for uttering the “I don’t know”.

The strategy for the discoverers and entrepreneurs is to rely less on top-down planning and focus on maximum tinkering and recognizing opportunities when they present themselves.

This idea that in order to make a decision you need to focus on the consequences (which you can know) rather than the probability (which you can’t know) is the central idea of uncertainty.

Summary

What is a Black Swan?

Our world is shaped by a continuous series of events and happenings. At first glance, it seems that these events are largely predictable and their consequences foreseeable.

But look deeper and we realise that our history is dominated by a small number of unpredictable, extreme events, termed Black Swans. These events are:

- Outliers- they lie outside the realm of regular human experience

- Extreme Impact- they have an outsized impact on the cumulative

- Retrospectively Predictable- we concoct explanations for their occurrence after they have happened.

The discovery of antibiotics, invention of the internet, and the creation of the laser, are all recent Black Swan events that have come to define the current age but were notably absent from the predictions of yesterday’s forecasters.

Why do we fail to recognise these Black Swans?

It may seem strange that we consistently fail to recognise the importance of events so large in impact and distant from the norm.

The reason for this is that our psychology includes a number of traits that distorts our perspective of them:

Problem of Induction

The first is that we learn from experience and thus have a tendency to project future events based on what we’ve encountered in the past. In fact, from our early schooling, we’re often told to learn lessons from history so that we don’t repeat the same mistakes.

This isn’t inherently bad- the problem arises when we think that the particulars of history can be generalised to the future.

This is the famous problem of induction- we must question our ability to infer future events from our flawed understanding of the past.

More worryingly, we tend to suffer from confirmation bias- discounting past evidence that may prove our hypothesis wrong and becoming increasingly blind to the limits of our inference for every historical event which confirms its validity.

In other words, we should not mistake “absence of evidence” for “evidence of absence”.

As Taleb describes, a turkey who is fed everyday by a supposedly caring farmer will infer that the feeding will continue ad infinitum. This belief will strengthen for every day the turkey is fed. Until Thanksgiving, of course, when a single, unpredictable event abruptly changes or rather ends the turkey’s life.

Similarly, a thousand successful voyages is not evidence of being unsinkable:

But in all my experience, I have never been in any accident… of any sort worth speaking about. I have seen but one vessel in distress in all my years at sea. I never saw a wreck and never have been wrecked nor was I ever in any predicament that threatened to end in disaster of any sort. E. J. Smith, 1907, Captain, RMS Titanic

just as a thousand white swans does not preclude the existence of a Black Swan.

Overconfidence in our knowledge of history makes us vulnerable to committing the same fallacy. It makes us blind to events which are outliers, outside the realm of previous human experience- it makes us blind to Black Swans.

Narrative Fallacy

Second, we love to simplify.

When presented with a sequence of facts, we find it irresistible to weave an explanation causally linking them together, no matter how far fetched.

This tendency isn’t entirely useless- the world is a complex place and reducing the dimensionality of information and creating explanations is our attempt to make sense of it all.

But as with the problem of induction, we often go too far. We let our imaginations run wild and concoct narratives even where they don’t exist.

Autobiographies of successful entrepreneurs often point to their unusual upbringing as causal factors to their success when thousands of others who had similar attributes tried and failed. Newspapers often attribute the daily movements of the stock market to a single factor without any evidence corroborating this.

And when a random Black Swan event does occur, we immediately attempt to rationalise it, to platonise it, to find a explanation on what caused it, even when there is none. In other words, we fall for the narrative fallacy.

Our explanations, irrespective of the truth within them, provides us with false comfort that we understand the origin of the Black Swan making them appear predictable only after the fact.

This illusion of knowledge makes us think that we understand these unpredictable events. Until the next one strikes.

Distortion of Silent Evidence

Third, our perception of extreme events is highly skewed as a result of our distorted view of the past.

When looking back, we only ever see the survivors. In reality, history is littered with even more who didn’t live to tell the tale.

Since we use historical data to predict the likelihood of future events, this bias often leads to skewed results. For example, we tend to evaluate the probability of an event from the perspective of the surviving parties, not the total number that started. This tendency, also known as survivorship bias, leads us to underestimate or overestimate the likelihood of a particular event occurring.

Take our own fates. Our forefathers had to survive war, famine, disease and other continuous threats of extinction. It seems like a miracle that we exist at all- at least when viewed from our perspective. But if we remember that we are the few survivors out of millions more who didn’t live to tell the tale, then the odds don’t seem so low at all- a small minority were bound to survive.

Or consider the literary success of authors. The vast majority of authors are consigned to small readership with little publicity. But ask a naive friend, unaware of the distortion of silent evidence, to estimate the likelihood of success and they will overestimate, evaluating from the perspective of breakout successes like JK Rowling and Stephen King whose names are plastered across bookstores.

Thanks to the distortion of silent evidence, “history hides Black Swans from us and gives us a mistaken idea about the odds of these events,”- it makes empirical reality appear more explainable (and more stable) than it actually is.

Consequences of Black Swans

The failure to account for Black Swans can have significant consequences, depending on the type of randomness prevalent in the domain.

Some classes of domains exhibit mild randomness, which Taleb describes as belonging to the utopia of ‘Mediocristan’. Here, the effects of individual events is negligible to the cumulative. For large samples, this means that the events will be clustered around an average, where no single event will change the aggregate total. Since uncertainty is mild, we can be comfortable in what we’ve learnt from data and so the common fallacies which afflict human kind (described above) are not as acute. In other words, extreme, random Black Swan events are either impossible or have negligible impact. For example, observations of weight, height, and the income of a baker all belong to Mediocristan- the extremities of any one of these quantities is unlikely to affect the average value.

In contrast, other domains exhibit wild randomness belonging to ‘gau’, where the effects of a single observation can disproportionately impact the aggregate. Since only a single event can transform the data, we cannot be comfortable with historical learnings and the mental distortions mentioned in the previous section can leave us exposed. History is directed by Black Swan events. Wealth, deaths from wars and financial markets all belong to the Extremistan.

Owing to his background as an options traders, Taleb particularly focusses on the endemic negligence of Black Swan events amongst risk analysts and forecasters in the financial markets.

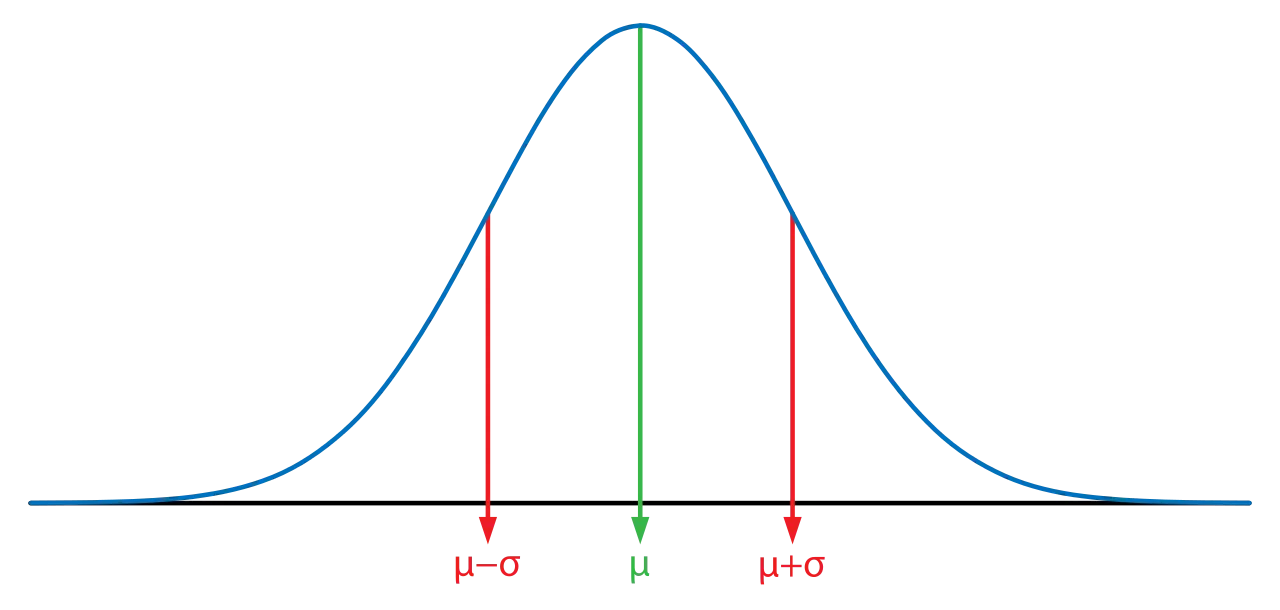

The inadequacy of the ‘risk forecasting and prediction’ models that are widely used stem largely from the ignorance of the differences between Mediocristan and Extremistan. These mathematical tools largely model the probability of events as a Gaussian distribution.

The Gaussian has two defining properties. The first is that most events have an expected value that corresponds to the mean of the distribution. The second is that the odds of finding an event which significantly deviates from the mean becomes exponentially smaller as a function of the size of the deviation. In human, this means that the occurrence of large outliers are very unlikely, and the more an outlier an event is, the more unlikely it becomes. Overall, the Gaussian universe is dominated by a large number of average events with the rare, largely irrelevant extreme.

The astute reader will notice that this matches the dynamics of Mediocristan, where Black Swans are either not present or their effect minimal. Indeed the Gaussian is a fine model for such domains.

But not in Extremistan, where rare, unpredictable, and extreme Black Swans dominate and direct history. The (mis)application of the Gaussian and its peers, Taleb argues, to Black Swan domains has resulted in catastrophic losses from the likes of bank failures, financial crises, and company blow ups, resulting from the failure to account for the possibility of these events. Since the Gaussian suppresses the magnitude of aggregate, the computed risk is essentially meaningless. What’s more is that these forecasts have an implicit error rate which increases as a function of how far in the future we’re trying to predict resulting in further divergence from empirical reality. The more into the future we try to predict, the more meaningless our forecasts become.

But then why do we continue to place our trust in these incorrect mathematical models?

One reason is the expert problem. In Mediocristan, historical experience is valuable and the word of an expert can be relied upon. For example, a brain surgeon (hopefully) knows a lot more about cognitive function that than a layman. In Extremistan, Black Swan events have no historical precedent; their time, location, and impact are unknown until they arrive.

This is clear if we look at the failure of so-called financial stress tests which subject financial institutions, often banks, to a simulated crisis of similar magnitude to the previous crisis to see if they would survive. The continued occurrence of crises as a result of Black Swan events is evidence enough that the properties of future extreme events is in no way limited by what has happened historically. In these expert-free domains such as risk analysis and financial market prediction, we forget that an expert’s knowledge over an amateur is an illusion since their historical experience provides little edge.

The recommendations of Nobel economists and other members of the academic elite who formulate and advertise the use of these predictive models should be heavily discounted. In a Black Swan domain, we are probably better served by our grandmother’s intuition.

These bankers and academics then rationlise their large losses, attributing it to a once in a lifetime event that has “has never happened before.” In other words, they attribute the failure to reality and not their approach. The model should fit reality and not vice versa.

What to do about it

As the maxim goes, the first step to solving a problem is to recognise it. And the second is to rectify it. Thankfully, Taleb provides direction on how to be robust, and even antifragile to Black Swans.

Firstly, we need to identify the class of domain which one is operating in. Only after classifying can we know the correct tools to use to handle the particular flavour of uncertainty. If we happen to find ourselves on the solid ground of Mediocristan, we can rely on our natural instinct and Gaussian modelling and be confident that our ignorance to Black Swans will go unpunished.

More likely, however is that we find ourselves in the unsteady waters of Extremistan.

The key insight to surviving in Extremistan is that the future is fundamentally unpredictable. Probabilities are incomputable- a single event, with no historical precedent can completely change the course of history.

Therefore, the use of any predictive model, no matter how mathematically exotic will not produce meaningful expectation values. The Gaussian cannot be used.

Instead, Taleb argues that the only way to account for possibility of Black Swans and capture the essence of Extremistan is to use a Mandelbrotian i.e. fractal approach, which models the expected values of events as a scale-free power law. Unlike the Gaussian, the odds of encountering an outlier decreases by a constant rate- this means that whilst unlikely Black Swan events are not suppressed and very much possible.

The Mandelbrotian is a descriptive, not a predictive model- it does not attempt to precisely predict when the next Black Swan event will occur but rather accounts for their possibility- the very fact that we know one is possible allows us to account for the possible consequences of such events. We do not know when it will happen but we can prepare ourselves for its impact.

This includes:

- Position yourself to benefit from advantageous Black Swans and avoid negative Black Swans- extreme events in industries such as the military, catastrophe insurance, and banking are likely to have mostly negative outcomes. In contrast, publishing, scientific research and venture capital will come with mostly positive outcomes.

- Use a barbell strategy- become very aggressive when you have limited loss and paranoid when you have the potential to be wiped out. One way to simulate this is by taking small highly aggressive bets e.g. investments whilst keeping the rest in safe- if you lose, you lose small. if you win, you win big i.e. convexity.

- Favour preparation over prediction- Don’t be narrow minded. Be flexible and be prepared- opportunity can come from any direction at any time.

- Seize any opportunity or anything that looks like an opportunity- increase your luck surface area and serendipity- you want maximum exposure to positive Black Swans.

- Beware of forecasts- be highly skeptical of those who claim to predict the future in Extremistan- don’t fall for the expert problem when encountering forecasts from academics, analysts or governments.

- Have epistemic humility- the presence of Black Swans shows that luck plays a much bigger role that we are often led to believe. To take advantage of this, we should favour intelligent, stochastic tinkering over highly directed research. Know that you don’t know.

All these approaches recognise the limitations of our knowledge and direct us to asymmetrically expose ourselves to positive Black Swans, where the result of many losses is dwarfed by a single large gain.

Subscribe

If you'd like to be kept in the loop for future writing, you can join my private email list. Or even just follow me on X/Twitter @yusufbirader.